Larry Long, ‘the American Troubadour,’ is giving a voice to the unheard

Larry Long’s entire archives will be digitized by the University of Minnesota Libraries over the next three years thanks to a $300,000 grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources’ Digitizing Hidden Collections: Amplifying Unheard Voices program.

The UMN Libraries announcement by Adria Carpenter reads, as follows:

Not long after his 20th birthday in 1971, Larry Long packed his life into his guitar case and left Minnesota to follow in the footsteps of his role model, Woody Guthrie.

He hitchhiked across the country, hopped freight trains, traveled with a fiddle player, and saw America in a way many people don’t. But no matter where he went, working-class people would always open their homes to him.

Long didn’t have much money, but he could make music. So before taking off, he wrote ballads on paper bags, in colored pencil with illustrations, and left them pinned to the fridge with a magnet as thank-you’s.

“I developed a deep loyalty to working class people because they had very little, but they always had room for one more at their table,” Long said. “I just wanted to give thanks to people, give gratitude for kindness.”

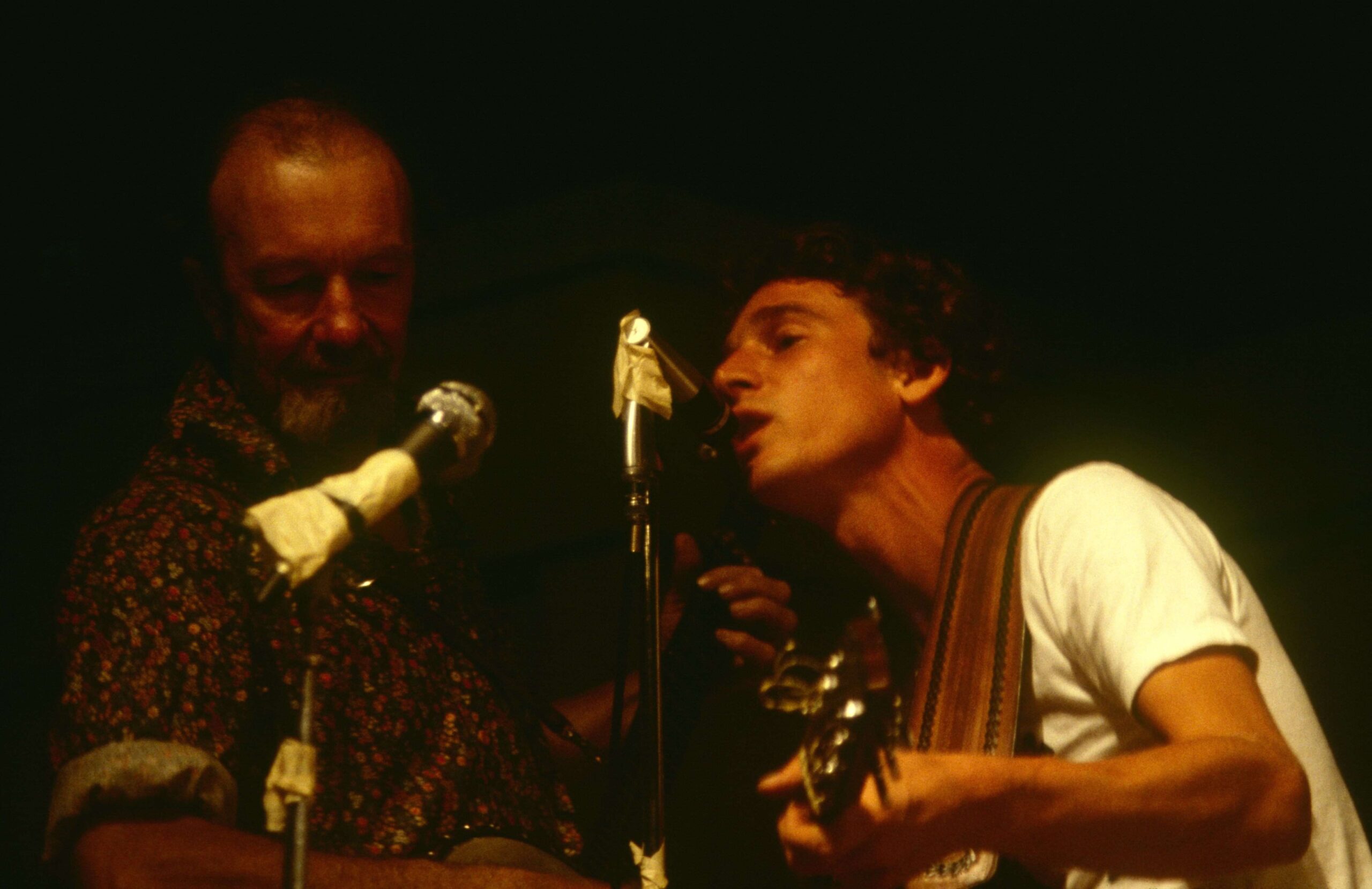

Now approaching 74, Long is an accomplished folk musician and singer-songwriter. He’s a Smithsonian Folkways recording artist, recipient of the Pope John XXIII Award and the Spirit of Crazy Horse Award, has performed the world across — including at Madison Square Garden with Joan Baez, Bruce Springsteen, and many others for Pete Seeger’s 90th birthday — and was inducted into the National Old Time Music Hall of Fame in 2014.

Long recently donated his archives of over 150 boxes containing media recordings, performance work, oral histories, letters and correspondence, and more to the University of Minnesota Libraries’ Performing Arts Archives (PAA).

His entire collection will be digitized over the next three years thanks to a $300,000 grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources’ Digitizing Hidden Collections: Amplifying Unheard Voices program.

“The gold of Larry’s work is that he is working with people,” said Deborah Ultan, curator of the Performing Arts Archive. “It’s the voice of the common family, the immigrant family. It’s about the families and individuals who have struggled to make a life for themselves … It tells a richness of our American history that could otherwise get lost.”

The working class troubadour

Long himself came from a working class family. His grandfather quit school in the sixth grade to work in the coal mines or Missouri and eventually resettled in Des Moines, Iowa, where he owned and operated a fish market.

Long skinned fish in the market for his grandfather, and it exposed him to people from different backgrounds, like the local Jewish and African-American communities. In their off hours, they volunteered in homeless shelters. After retirement, his grandfather became a street preacher and working class poet.

“A lot of his family drank pretty heavily, so he laid down the bottle and picked up the Bible with the same fervor,” Long said. “He just had a really strong ethic about human decency. I really cherish those times in Des Moines.”

But when Long was around 10 years old, his father, a Hills Bros. Coffee salesman, got transferred to Minnesota, and they found a new home in St. Louis Park. Two years later, his father passed away; Long and his two sisters were raised by his mother.

They didn’t have much money, but people in the community — small grocery store owners, friends and neighbors, people who knew his father, members of his mother’s church — gave what they could to help.

“My father died young at 36, so I thought that I would die young too. I never thought I would live to be older than my father,” he said.

‘That’s what I want to do’

Around this time, Long started writing his own music. Growing up in the Baptist churches of Des Moines, Long listened to old hymns like “Just a Closer Walk with Thee” and “I Surrender All” that still resonate with him.

But his real musical impulse came from his parents. His mother was a pianist, and his father loved to sing around the house and listen to Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, and Dean Martin, though Long preferred The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan.

It was through Bob Dylan that he discovered Woody Guthrie, and Long developed an immediate kinship. Long and Guthrie both grew up in working class families in America’s heartland and had difficult childhoods. So reading Guthrie’s autobiography, “Bound for Glory,” was a watershed moment in his life.

“When I read that book I said, ‘That’s what I want to do.’ So that’s what I did,” Long said. “Woody Guthrie wasn’t writing songs to become commercially famous. He was just very loyal to the people that helped him out, the good working class people, everyday people, neighbors.”

“And I had that same passion in my heart. I wanted to thank people who’ve been good to us,” he continued. “I just wanted to go out and hit the road and just get to know America in the same way that Woody did.”

Follow your bliss

In 1979, Long joined the Tractorcade protest, organized by the American Agricultural Movement, where thousands of farmers led a convoy of tractors to the nation’s capitol, demanding higher pay for crops and a voice in agricultural policy decisions.

There, he met Pete Seeger and learned about his environmental advocacy. Seeger inspired him to organize the Mississippi River Revival, a decade-long cleanup project. From there he met Amos Owen, a Dakota elder from the Prairie Island Indian Community in Minnesota, and got involved with the American Indian Movement, writing songs with and for them.

And from his musical advocacy, Long was invited by the Oklahoma State Department of Education to travel throughout Oklahoma writing songs with students in the tradition of Woody Guthrie. There he organized the first hometown tribute to Woody Guthrie in Okemah, Oklahoma, which today has become the annual Woody Guthrie Folk Festival.

Long continued his educational work in rural school districts throughout Minnesota, South Dakota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Nebraska, California, Georgia, and Alabama. Long later received the Bush Artist Fellowship and recorded two albums with Smithsonian Folkways. One song, entitled “Hey Coal Miner” was released on the Smithsonian Folkways Children’s Collection, along with works by Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Ella Jenkins, and others.

“All that happened like a river because I followed my calling,” Long said. “To all the young people, follow your bliss. Do what you do, not so much to make a living, but to make a life. And if you do what you love, you’ll have a wonderful life.”

Crossing lines of complexion

While working in Alabama, Long created Elders’ Wisdom, Children’s Song, an intergenerational program that brings elders into the classroom to share their stories, so students can learn about each other and their communities.

The program developed from Long’s relationship with indigenous people, specifically Amos Owen, with the goal to honor people of all nations and cross lines of complexion, like class, culture, gender, and so on.

“What better way for kids to learn about each other than through the voices of their elders,” Long explained.

Four elders from different backgrounds and perspectives visit the students to give them a broad understanding of their neighborhood. At Prairie View Elementary School, in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, for example, students listened to Helen Tsuchiya’s story about living in the Japanese-American internment camps.

“We urge the elders to talk about struggles in life, to go deep into those things that are tough, which ends up helping students who are struggling in their own life,” he said.

The interviews are recorded and transcribed, and the students use them to create songs based on the elders’ experiences. They break the transcripts into themes, which become the verses, while the elders’ words of wisdom become the chorus.

“Spoken word connects to the folk process, in that when you hear me speak, there’s a melody to how I talk. And if you listen closely, you can kind of feel the breath and the notes,” Long said. “There’s a sense of melody and beauty to everyone.”

Once the songs are finished, the class hosts a celebration for the elders and their families. The elders receive a rose and a copy of the song lyrics, and the students sing the songs to the elders.

“It moves from students getting to know each other, to the community getting to know each other,” Long said. “A lot of transformation comes out of this process.”

The St. Louis Park Public School District has adopted the program into its curriculum, and school systems across Minnesota have followed suit. Long hopes to teach his process at the University of Minnesota to educators, so that it can be replicated throughout the country.

Make room for the stranger

Long donated his archives to the Performing Arts Archives, not so that it would be merely preserved, but so that it would be a “living archive.” He hopes his materials will be useful, accessible, and meaningful to people.

“My hope for this archive is that it doesn’t get stuck in a box at the University, but that the archive expands like a web that connects communities to institutions and institutions to communities,” Long said. “The best outcome of my work is that it may inspire others to maybe look at life a little bit differently … The greatest thing an artist can do is inspire someone else to create.”

The majority of the CLIR Grant will support the digitization of at-risk media, Ultan said, like old reels, cassette tapes, and videos. They’ll use another portion to hire a project specialist who will process the archive and work with Ultan to curate an exhibit, which will open in 2028 and coincide with Long’s 75th birthday.

Getting his work digitized and available worldwide has been “a fulfillment of a dream” for Long. With this grant, everyone will have access to his archive, especially those he has long collaborated with – the immigrant and working-class communities who have always welcomed him – as well as large institutions like the Woody Guthrie Museum, the Smithsonian, and the Minnesota Historical Society.

Now an elder himself, Long has his own words of wisdom he wants to share with the next generation: “to listen, to suspend judgement, to make room at your table for the stranger, and to move through life with a great kindness and compassion for those who do our work.”